San Antonio is hoping career-themed schools can alleviate a worker shortage and lift graduates into well-paying jobs

SAN ANTONIO, Texas — CAST Tech, San Antonio’s newest public high school, looks like an outpost of Google. Young people huddle over tablets, fiber optic cables run along the ceilings and a cybersecurity lab occupies the basement.

The school, located in the heart of San Antonio’s slowly revitalizing downtown, is just a stone’s throw from some of the city’s big employers. The financial firm USAA has offices five blocks away, and Frost Bank and tech incubator Geekdom are nearby, too. This makes it easy for business executives to pop by — and they do. In its first academic year, the school entertained dozens of local business leaders as guest speakers and, nearly every week, students welcomed tech employees who serve as mentors.

All of this is by design. CAST Tech, which opened in fall 2017 with 175 freshmen, is the first of three career-themed public high schools currently planned for San Antonio. The schools are the brainchild of Charles Butt, a big donor to local education causes and chairman of H-E-B, the region’s largest grocery store chain. After having trouble finding skilled employees for his corporate headquarters, Butt brought together San Antonio school superintendents, business leaders and workforce experts to explore school models that could give students the academic foundation and skills required for jobs in fast-growing, well-paying local industries.

Their answer was CAST (which stands for Centers for Applied Science and Technology). The schools are intended to prepare students from across the San Antonio metro area for careers in tech and business, health care and advanced manufacturing. They rely on industry “partners” — 10 so far at CAST Tech — to guarantee students internships and mentorships and to help keep the curriculum current. Students take a mix of core academics and classes such as entrepreneurship and graphic design; in addition, they can earn up to 30 college credits through dual enrollment programs with local colleges.

Modeled in part on California’s High Tech High charter network, business-backed programs in Georgia and South Carolina and STEM programs in Massachusetts, the school are part of a growing push to more closely match the skills students gather in high school with workforce needs. While some educators worry about turning schools into vehicles for job readiness, efforts to integrate technical training and academic education continue to gain traction. A recent White House proposal to merge the education and labor departments into a new Cabinet-level agency, the Department of Education and the Workforce, underscores the popularity of this view in Washington.

In San Antonio, the CAST schools are also one prong of a larger effort by a local school district to promote integration in one of the most economically segregated cities in the country. The San Antonio Independent School District, which will operate two of the CAST schools, is one of 19 school districts in the county and among its poorest. Mohammed Choudhury, who joined the district last year as its chief innovation officer, wants to ensure that these and other specialized schools in his district avoid some of the common pitfalls of school choice.

“Usually when districts launch specialized initiatives around school choice, and resources are put into the school in an urban environment, they end up exacerbating segregation that already exists,” he said. But while CAST Tech encourages applications from across the metro area, it eschews the admissions exams used by magnet schools, and, unlike most charters, is run by the school district. Plus, Choudhury solicits applications from the city’s poorest pockets, and carefully tinkers with the mix of students from low- and middle-income families.

One year in, that approach to economic integration, dubbed “diversity by design,” is working. However, the specialized schools under Choudhury’s purview, including CAST Tech, have met resistance from locals who worry that they are sapping resources from the district’s existing neighborhood schools.

Choudhury, though, is adamant about the value of economic integration — and the importance of giving low-income students, in particular, access to educational options. This includes the specialized tech skills and business networking opportunities ingrained in the CAST Tech model.

At CAST Tech, even P.E. has a tech focus.

One school day this spring, a beeping sound comes from under freshman Toney Coronado’s shirt. A monitor she is wearing as part of a PE project is going off, informing her she has reached her resting heart rate, and cueing her to make a note of her current activity. Toney apologizes, resets the monitor, and moves on to explain how she came to CAST Tech.

Toney lives in the North East Independent School District, a relatively affluent section of the city with well-rated schools. But she said she wanted more than strong academics. The 15-year-old also sought real-world experience in her desired career: cybersecurity.

“I thought that CAST would be a better opportunity for me,” she said. She’s always loved the idea of cybersecurity — being a good guy hacker. Getting a job in that field will require more than just technical skills though. CAST Tech also helps with the nuts and bolts of the application process. Coronado recently showed her mom a mock resume she’d been working on in “principles of business,” a required class for freshmen. “My mom was shocked,” Toney said, laughing. The quality of the resume was so good, so professional. “She wants me to help my older brother.”

In addition to her classes in English, history, algebra and life sciences, Toney will have the opportunity to earn a “Red Hat Certification” in cybersecurity, a competitive credential in the field.

“They are teaching strong fundamentals,” said Bret Piatt, chief executive of Jungle Disk, a startup cybersecurity firm. The average annual salary at his company is $75,000, well above the median income of families in the San Antonio Independent School District, which is roughly $32,000, and the $56,000 median in the San Antonio metro area. Piatt says he plans to recruit from CAST Tech in the years to come.

CAST Med, scheduled to open in the San Antonio Independent School District in the fall 2019, will prepare kids for midlevel careers in the booming healthcare field, such as nursing, anesthesiology, and phlebotomy. Manufacturing jobs, which pay a median local wage of $42,952, are growing quickly too, by 8 percent over the next six years. CAST STEM, focused on advanced manufacturing, will open this fall in the city’s Southwest Independent School District, a more rural district with a high percentage of low-income students.

While CAST encourages input from industry partners on the curriculum, so far there’s been no evidence of any concern that the schools are giving businesses too much influence. That may be because, for all the focus on professional preparation, the schools are also giving students the academic education to equip them for college — not just the workforce, say CAST leaders. As more and more jobs require some education beyond high school, Pedro Martinez, who joined the San Antonio Independent School District as its superintendent in 2015 urges all students to consider earning a college or post-secondary credential. At CAST Tech, said principal Melissa Alcala, “We’re trying to prepare them for both tracks.”

Choudhury acknowledges that companies could see the schools as labor farms for whatever jobs they happen to have, but added the schools’ goal is to educate children for jobs that will help move them out of poverty, not keep them in it. “Let’s not launch these [career-and-technical education] programs to give employers a new assembly line.”

Another risk, Choudhury says, is complacency about who gets to attend.

When he arrived in San Antonio in April 2017 after three years with the Dallas public school system, CAST Tech was in the middle of enrolling its inaugural class, Choudhury said. He looked at the demographics and began to worry. By simply opening up admission to all and seeing how “it plays out,” he said, the school was attracting plenty of teens from middle-class families but few from the district’s poorest neighborhoods.

Almost immediately, he began calling low-income families whose children had been admitted but had yet to accept. Failing to follow-up, he explained, ends up excluding low-income families who may lack voicemail or the ability to regularly check email. Choudhury personally called families until someone answered. He also began pulling low-income families off the waitlist as spots became available. The result: District data shows that CAST Tech’s first class was split evenly between families earning above and below $44,000 per year. Roughly 60 percent are from the San Antonio Independent School District and the rest are from outside the district.

Going forward, Choudhury said he and his staff will carefully monitor the enrollment process and promote the schools in neighborhoods with uneven access to internet, social media and other information platforms, going door to door if they have to. Then they’ll hold separate lotteries for students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch and those who don’t, to ensure that the second batch of students accepted is roughly a 50-50 economic mix. Next they’ll take a closer look at those enrolled to ensure that at least 12.5 percent of students come from the deepest pockets of poverty in the city. When skeptics ask why CAST emphasizes socioeconomic integration, Choudhury points them to studies showing that kids of every income level thrive academically and socially in economically integrated schools.

Building these attractive schools, however, takes money; to get those dollars, the schools needed a rainmaker and found one in Superintendent Martinez. The CAST schools underscore the fundraising success of Martinez, who was hired three years ago from the Nevada Department of Education. In that time, giving to the San Antonio ISD Foundation has risen from $919,520 in 2015 to more than $11 million last year. Gifts to CAST schools since 2015 have totaled $10 million, including a $3.6 million donation from H-E-B in 2016.

But all that giving has come at a price. Some teachers and other district residents worry that the specialized schools are pulling attention and money from neighborhood schools.

“My concern is that the district, in its attempt to be innovative, has created all of these specialty schools at the cost of the neighborhood school,” said Candace Michael, who retired from teaching in the San Antonio Independent School District and is now an educational consultant. “They get everything they need or want.”

The district has plans to improve the rest of its schools, filling them with effective teachers, and allowing campuses to apply to become part of Choudhury’s “innovation zones,” whose schools have longer days, weeks and even school years. Few of these schools are as high profile as CAST Tech, however, and none has the same level of philanthropic investment.

“We have to do high-poverty schools well,” Choudhury said of the existing district schools, where roughly 90 percent of students are low-income. “At the same time, we have to stop recreating them.”

In addition to CAST Tech, the San Antonio Independent School District recently opened four other so-called “diverse by design” schools, including two dual language academies. It has more in the works, including more dual language schools and another CAST school, CAST Med.

One of the district’s strategies to help all schools improve is to recruit “master teachers.” Specializing in high-demand subjects, these teachers work longer school days to give extra help to struggling students. In turn, master teachers earn extra stipends of up to $17,000 per year, on top of the average salary of $55,000 (roughly $2,500 higher than the state average).

Of the nine teachers hired to launch CAST Tech, seven are master teachers, and half hold master’s degrees in educational technology. This allows them to incorporate advanced technology — web-based interactives, gaming — into humanities and algebra in a way that engages their techy students, said Alcala, CAST’s principal. It also allows them to tailor lessons for students and help them learn at their own pace.

The importance of that customized education has become increasingly apparent. Because the school doesn’t screen for admission and draws so many students from the San Antonio Independent School District, many freshmen arrive unprepared, Alcala said. Last school year, nearly 20 percent of district schools failed to meet state standards, placing them in the bottom 5 percent of Texas schools.

“We’ve got kids who have been in this district and they have not passed a reading [state accountability test] since they started taking them in third grade,” said Alcala.

The more personalized experience allows all students to stretch academically, she said.

Madisyn Holveck, a freshman, mastered a year-long graphic design curriculum in one semester. Her teachers encouraged her to enter design contests — and she won the chance to design a logo for King Ranch, a Texas institution.

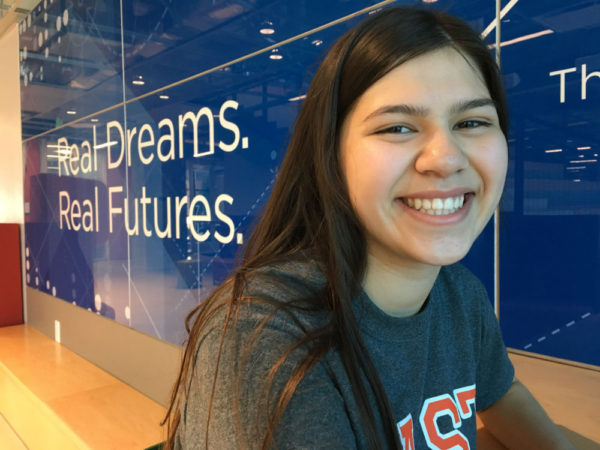

On a recent Tuesday, Madisyn was one of 30 CAST Tech students on a field trip to a Microsoft store, where they got to test drive some of the company’s newest products. Wielding a stylus like a pro, Madisyn tried the latest model of the Microsoft Surface, to see how the laptop compared to the Chromebooks and Macs she works on at school and in her design class.

Field trips like this highlight the economic differences between the students.

Before the field trip, Kevin Castellano, a freshman, had never been to a Microsoft Store. In fact, he said he had never been to La Cantera, the posh North Side shopping center where the Microsoft Store is located.

“It’s so far north,” said Kevin who lives on the city’s East Side. He glanced around the store: “It’s so … sleek.”

Had he attended Sam Houston High School, his neighborhood school, he said he would miss out on the diversity of experiences he’s had at CAST Tech.

The school offers plenty of extra-curricular activities, including Toast Masters, camping, mock interviews and lacrosse. These activities give students access to the same opportunities as wealthier peers; when they enter the workplace, they’ll feel comfortable among co-workers from more privileged backgrounds, Alcala said.

To really accomplish its mission, the school has to pay attention to more than gaps in test scores. “There’s so many places where income disparity shows up,” said Kate Rogers, a former H-E-B executive who helped start the CAST schools.

CAST Tech is trying to erase some of those disadvantages, and that’s not lost on the students. “What’s cool about CAST Tech?” asked a Microsoft employee, advising students to brag a little about their school on their LinkedIn profiles. Madisyn, already thinking about how to market her freelance work, had been listening closely. Her hand shot up. “It’s locally recognized,” she said. “When businesses see you went there, they might give you preference.”

That sums up the appeal of schools like CAST Tech. And plenty of people are hoping they deliver.

Source: Hechinger Report By: Bekah McNeel