My Dad died this week of cancer, and these days, when I wake up, my world feels like it has dimmed a little from the loss of his light.

My earliest visual memories of my Dad are fuzzy images of a big tall guy who seemed larger than life to me, who sometimes came home late but always had energy to pick me up and swing me around, throw a ball, or read a story aloud using funny voices (he could recite the Grinch Who Stole Christmas from memory, something my children also enjoyed) with a goofy sense of humor and mischievous glint in his dancing eyes. When he transformed into the Tickle Monster, we were simultaneously delighted and terrified.

Dad always had a tiny bit of a gut and could never resist a self-deprecating joke; he loved to say: “I’m a Coors jogger. When I get the feeling to exercise, I lay down on the couch, open a Coors, and wait for the feeling to go away.” He would follow this proclamation with a big booming laugh (which sometimes preceded the punchline), and sometimes actually crack a beer and flop onto the couch to punctuate his point. Despite his alleged aversion to exercise, he loved sports, especially the social ones: tennis, skiing, and golf.

I am not sure if I naturally gravitated toward sports or if I faked an interest in baseball to gain his attention. He was determined that I not “throw like a girl,” a phrase that surely would be frowned upon today, but unerringly predicted what would be the basic test of entry into a boy’s sport. When I did sign up for Little League, he encouraged me, and I was eventually one of 2 remaining girls on my team. One day, I confided that the boys were calling me a “lez;” in a characteristic response, my Dad listened, explained what that word meant, and supported me until I chose soccer over baseball – but on my own terms.

As I grew older, I would ask myself if my Dad was a feminist, or if he was just making space in a man’s world for the daughter he loved. After his diagnosis, I put together a playlist of music he played when we were kids, and was struck by his fondness for musical theater and anthems about feisty women: “Anything You Can Do (I Can Do Better),” and “I’m Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair.” My dad loved silly songs, like the Chad Mitchell Trio’s “Lizzie Borden,” and he loved the singers of his era, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger and especially Harry Belafonte. (He even sang along to “Free To Be You and Me,” though those hippie gender-bending jams were likely more my Mom’s influence.) These past few months, as his light was fading, we would sing together to the playlist, our shared inability to carry a tune still good for a laugh.

During a club soccer game in high school, I collided with a player much larger than I and broke my leg in 2 places. An ambulance was called, but the next thing I knew, my Dad had driven our Pinto out into the middle of the field and was gently loading me into the back so he could transport me to the hospital himself. While Mom would follow the picayune details of our life, remember the names of each of our friends – and their friends –, and manage our social calendars, Dad could be counted on to take my side even if I was in the wrong. For my entire life, my Dad has been the guy who asks no questions but comes in with a big hug, and a shoulder to lean on.

My parents built a small A-frame ski lodge together, and it was a place they loved to host friends on the weekends. My Dad first took me to the slopes when I was 5. He may have decided against lessons because of his legendary frugality, but he was also a patient teacher. He wrestled me up the T-bar, only for me to arrive at the top of the mountain and announce my need to pee. Undaunted, he corralled me between his legs and skied down the entire mountain with my tiny snowplow inside his big one.

My dad did have a temper, but I really only remember him blowing up at me once. Unsurprisingly, it was my brother Gordon’s fault. Seriously, as the older sister, I had the misguided notion that when my brother got in trouble, I would save the day. But jumping in to fight my angry Dad backfired. He chased me down the hall, and I holed up in my room for 24 hours until he cooled down.

My dad loved people, and hosting parties. Growing up, I recall being sent to “the kids room,” just far enough away that we could hear one voice rise above the din. There would be a pause as he concluded his joke, and in the silence, we’d hear my dad’s distinctive laugh and a long beat before the others followed.

These qualities I found so cringeworthy as an adolescent are among my most treasured memories of a man who gave people affectionate nicknames (mine was “Beans,”) and loved playing games (not the word games that my mom’s family excelled in; he was a terrible speller) but especially cribbage, which gave him pleasure even in his final months. My Dad was famous for topping off everyone’s wine glass, a habit that was dangerous for me until I learned to pay very close attention, but which spoke to his desire to stretch the moment, for folks to linger and to share just one more story.

The last trip we took as a family was to see Gordon at his new job at the Boston Globe, and we drove up to Bowdoin College in Maine to see my son Marcos, a freshman. My dad also attended Bowdoin, where he played a lot of sports, bridge and cribbage. There is one picture of him studying in his room at the Chi Psi fraternity. It’s possible the photo was staged for his parents’ benefit, because after the end of his sophomore year, they received a letter letting them know that he would not be asked to return for his junior year because he had failed too many classes.

On our trip to Bowdoin, he recalled the letter as a wakeup call, and thought someone from Bowdoin might like to hear his redemption story of transferring to a technical school to earn a degree as a plastics engineer. I offered to help him by writing his story, but he said simply: “I’m a people person. I like people.” He also loved animals, though he would deny it, and could often be found with our dog at his feet and our cat purring on his lap while he stroked its head and said: “I don’t know why this cat doesn’t realize I hate her.”

Dad worked long hours; he started his career as a scientist, but a perceptive mentor recognized his gifts as a storyteller and networker, telling my Dad, “if you could manage, you could manage..” We spent two years in St. Louis before my Dad was offered the promotion that catapulted his career. For reasons I can’t recall, we assembled for a family vote on whether to stay or go. The 4 of us cast our votes, and my Dad and I voted to move. I don’t remember how we determined the winner, but I do remember catching my Dad’s eye across the table, and his tiny smirk was like a secret signal acknowledging that we were kindred spirits – the two adventurers in the family. It was one of the many times my Dad gave me permission to be a person who took risks, even if sometimes he would say: “you scare me, Jeannie Russell.”

Before I went to college, my parents gave me a checkbook and taught me to balance it. They insisted that my brother and I know how to budget, that we understand how to invest, and when I had my first job, my Dad insisted I take the 401K match, even though I was barely covering rent and expenses. Neither my brother nor I chose lucrative career paths, but our parents drilled into us the importance of savings, and made it possible for us to live a good life even as we pursued a calling.

My parents were frugal, sometimes to the point of absurdity, but they were also exceedingly generous. They were willing to spend money on family trips, which started with road trips, often to national parks, in the station wagon, and as my dad accumulated frequent flier miles, trips to Canada and Europe. My Dad grumbled that we treated his miles “like candy;” but his constant traveling afforded me the ability to move to first Japan, then Guatemala, more for the experience than for the money. In Japan, I lived sparsely in a tiny tatami room apartment with my college roommate, knowing that my meager savings in yen would translate into many more dollars at home. My dad finagled a trip to Tokyo while in another part of Asia, one of our few solo adventures. He had an expense account and treated me to crab Shabu Shabu, one of the best meals of my life – and it cost as much as I earned in a month. Once we were adults with children of our own, his greatest pleasure was to host the entire family on trips to his favorite places, and he eagerly anticipated when the youngest, Marcos, would be old enough to safely join an African safari.

Dad had a remarkable journey from plastics researcher to vice president of commercial development, crafting joint ventures to build semiconductors across Asia. While he loved to tell stories of the wonders he had seen, he was a humble guy who always referred to himself as a “peddler.”

The person my Dad most admired was his own father, Daniel Russell, who had immigrated to the Boston area from the Gorbals area of Glasgow, Scotland in his early 20s. A singular regret was that his father, who died at age 62 after multiple heart attacks, did not live to see his son’s success. His father worked in the shipyards along the River Clyde as a youth, then trained as an engineer. He was drafted into the Royal Air Force during WWI as an airplane mechanic. However, persistent lung problems stemming from his time in the shipyards combined with the difficult labor conditions of the Great Depression meant he struggled to find consistent work after immigrating. An inveterate tinkerer and inventor, he manufactured fireplace bellows in his basement, using his son as an apprentice, and took up a variety of other skilled craftsman jobs in the Beverly area.

Like his father, my Dad could make or fix anything, and starting when we first lived on our own, he began to make us furniture. My first studio apartment in New York City was the size of a postage stamp, so my Dad made me a genius folding table that was like origami, it folded up and tucked itself away neatly. I still have that table today. He helped my brother and I remodel multiple homes, building or re-doing cabinets, porches, bathrooms, and more. He offered every person in our extended family one piece of hand-made furniture. After his diagnosis, he worried that a favorite niece (of course they are all favorites) had been uncertain as to what to ask for, so never got her piece. He insisted that she pick an item from my parents’ own collection to ship before his death. At one point, he seemed to grow bored with our pedestrian requests, so Mike and I challenged him to make a table shaped like a fish. Would you believe that UPS lost this table, prompting my father to ultimately send a letter to the president of the company, and of course, build us a second fish table? I could never figure out whether he intended the letter to be hilarious, or whether it was just a happy accident. It was sprinkled with phrases like: “But I am writing to you because I think your processes need improvement,” and “Obviously, I would also like you to find my table.”

He built all these beautiful hand-crafted pieces using hand-made tools his own father fabricated. In addition to furniture, my Dad made thousands of glasses from wine bottles, and he loved to gift them far and wide, joking: “they have a lifetime warranty – my life, not yours.” (The last person he gave them to was one of his caregivers.)

Both my parents are doers, people who will roll up their sleeves and do what it takes. One of my Dad’s favorite stories to tell was about the time he and my Mom came to help me out in San Antonio after the birth of my first child, Bella, when I had to return to work. They had barely arrived when my Mom’s Dad suffered a stroke, and she immediately left to care for him. I remember coming home to find my father swinging on the porch with my tiny daughter, or rolling around on the floor, embracing new skills outside his comfort zone with joy. It may have been the first time he ever changed a diaper; certainly it was the first time had ever been the chief caregiver for a newborn. My parents came to San Antonio regularly to help me as an adult; they were my first call when I broke my ankle playing soccer in my 40’s, and they came and blockwalked when Mike ran for mayor.

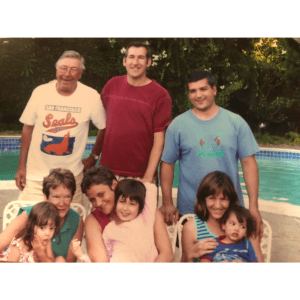

Cancer is the most brutal disease, especially toward the end. But the diagnosis 9 months ago was a signal to my family, already close, to treasure this remaining time together. Not only did my Dad once again bring us closer together, but he also sparked my college roommates, my roommates from Guatemala, my closest friend for forever, high school friends and more, to reach out – because he was a huge presence in their lives as well. My Dad did not take for granted that he had lived a remarkable life, just as I do not take for granted how special it was to have a Great Dad. One of my favorite memories of my Dad is when he walked me down the aisle – he was proud, excited, and slightly teary. I went to look for a photo of us together on my wedding day, and instead I found this photo: my Dad caught mid-story – I can’t think of any better way to remember him.

Jeanne Russell

Executive Director

CAST Schools